The exhibition

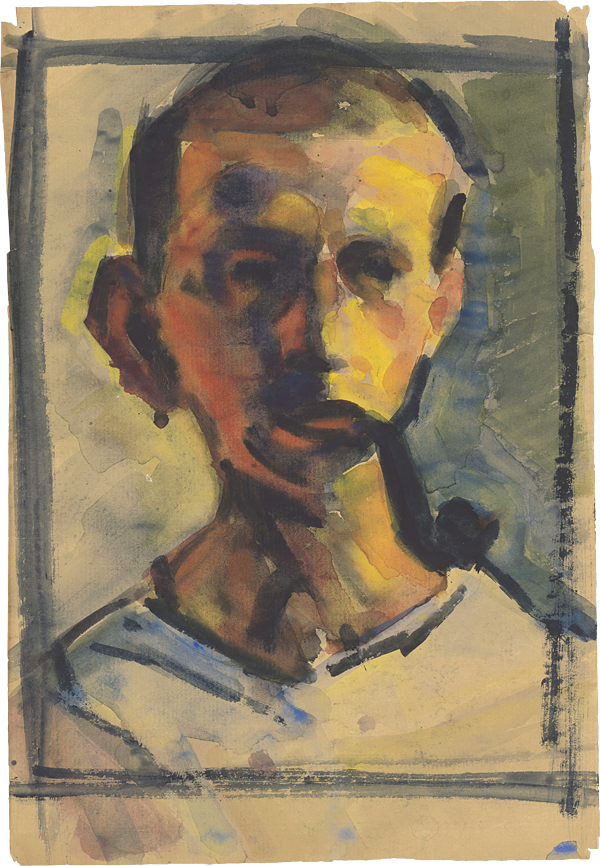

Without doubt, Hermann Glöckner (1889 Dresden – 1987 West Berlin) is, today, to be considered one of the most exceptional artists among the avant-gardists of German Classic Modernism. Despite adverse political circumstances under the National Socialist dictatorship and the GDR regime that followed it in East Germany, he worked continuously in isolation in Dresden over the decades as a “noncomformist” and created an outstanding artistic oeuvre that still awaits discovery.

For a long time, Glöckner’s works fascinated artists, first and foremost. Even today, Hermann Glöckner is preceded by his distinctive reputation as an “artists’s artist.” At the same time, he stood in the shadows of the established masters of Classic Modernism, almost unnoticed in art history. Only in the past few years has his singular artistic contribution been placed within broader intellectual and artistical contexts and also presented to an international public as a new discovery.

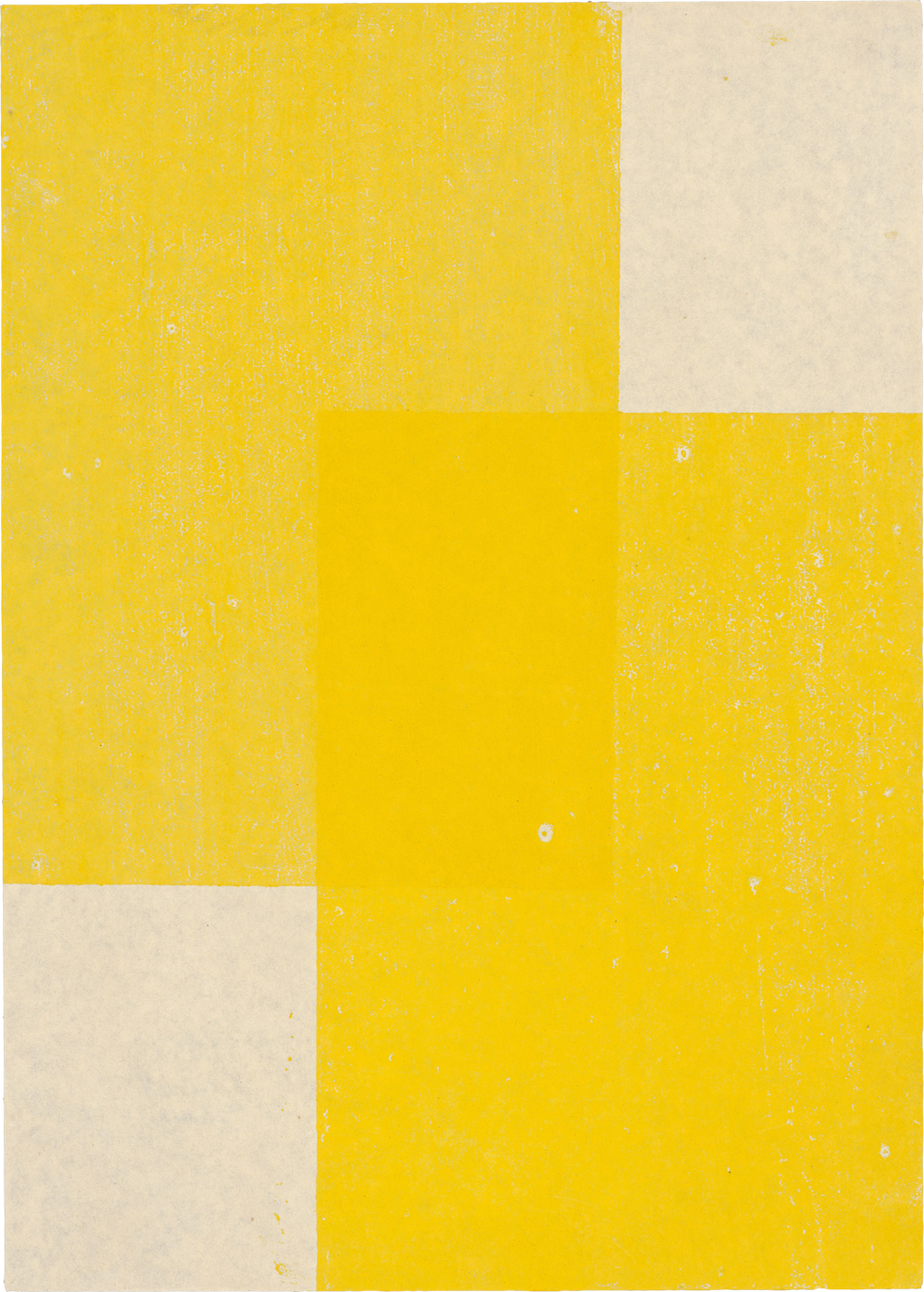

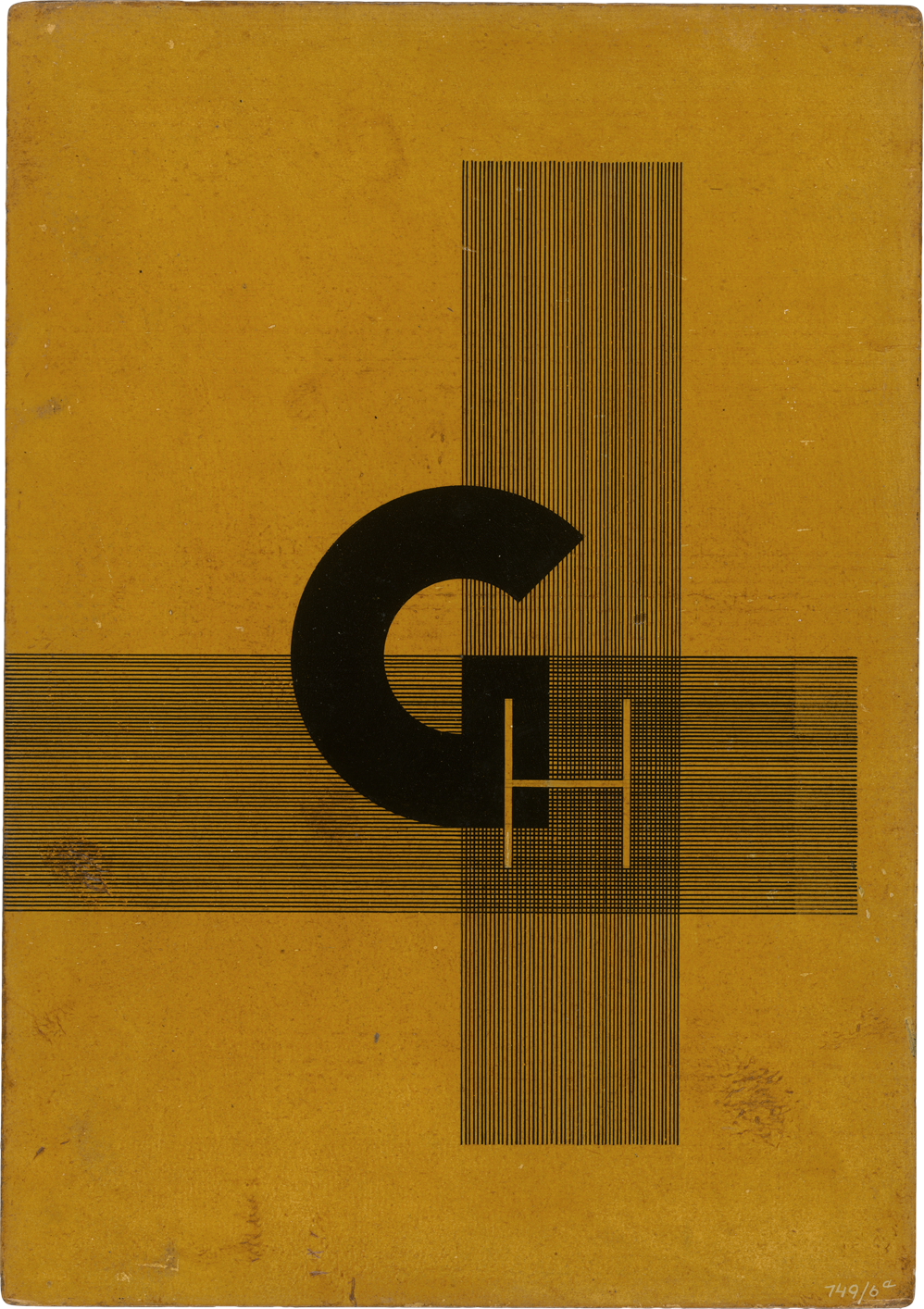

In the Munich exhibition “Hermann Glöckner—A Master of Modernism,” examples of his early “Tafelwerk” (Panel Work) from the period between 1930 and 1935 are presented together with a group of his “Modelli” (Models) of the 1960s and 1970s, which can be understood as drafts for the large-format, sculptural folded works he conceived. For the first time, these central groups of his abstract-constructivist oeuvre have become the subject of a focused art historical examination. Both must be understood as continuing artistic and conceptual studies that were a source of inspiration of great importance to Hermann Glöckner and at the same time are keys to understanding his entire oeuvre.

Planning your visit

Open today till 6.00 pm

Daily 10.00 – 18.00

Thursday 10.00 – 20.00

Monday closed

Barer Straße 40

80333 München

Sunday admission 1€

Thursday – Saturday 10€

reduced 7€

Day pass (Alte Pinakothek, Pinakothek der Moderne, Museum Brandhorst, Sammlung Schack) 12€

Against this backdrop, the selection of the early panels concentrates on the years 1930 to 1935. That is precisely the period in which Glöckner began to record the vocabulary of his creative ideas in a group of studies that will be later called his “Tafelwerk.” Its genesis had been proceeded by a crisis the artist went through, after which he found a completely new approach. Like a vocabulary, Hermann Glöckner inscribed his newly acquired artistic insights and creative ideas in the panels. After 1945 he continued this “Tafelwerk” at even greater intervals and in several creative phases, varying and expanding the themes. Glöckner regarded the panels as a genre of their own. Despite this formal-constructive rigor, their reworking articulates a playful, intuitive legerity. This supposed artistic and conceptual dissonance is constitutive of Glöckner’s entire oeuvre without which this variance in the design of the works would be inconceivable. This becomes evident from a dazzling group of exhibited drawings, monotypes, and collages by Hermann Glöckner that have been acquired gradually over the past three years by the Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München and that exemplarily cover his entire creative career from the 1920s to the 1980s.

Photo: State Graphic Collection Munich

© VG Picture Art, Bonn 2019

Photo: Werner Lieberknecht

© Werner Lieberknecht, Dresden

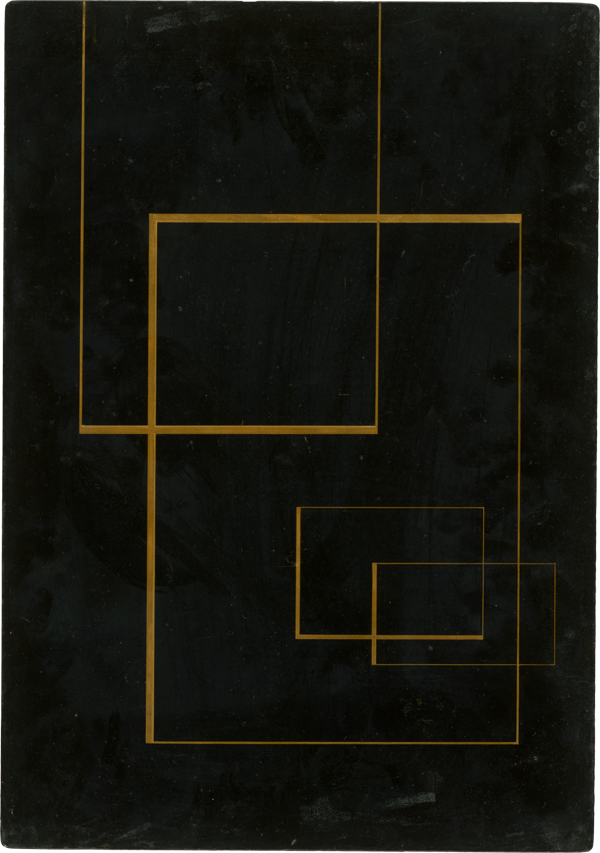

The second part of the exhibition, which features Hermann Glöckner’s “Modelli” of the 1960s and 1970s, looks at the point of departure for his spatial, plastic folding of paper, pasteboard, and cardboard. They are scarcely conceivable without the constructive and artistic research of the early “Tafelwerk.” At the same time, like the panels, they form a kind of vocabulary and are created within the context of other spatial, plastic objects. With his characteristic playful rigor, Hermann Glöckner continued his early “Tafelwerk” research in the “Modelli,” albeit now in sculptural form. The temporal distance between the two groups of works is not very surprising if one considers that, in the meanwhile, the artist had had to take on practical building projects that drained his energy, in order to secure his financial existence.

In their material simplicity, the “Modelli” still radiate the lack of artistic constraints in their characteristic sketching of ideas, in which unconventional artistic experiments can be freely explored and greatness imagined in small. In his studio, which was in essence limited to a large room in the Künstlerhaus Dresden-Loschwitz, they were omnipresent on the tables, and Glöckner truly plunged into this world of ideas.

That Hermann Glöckner’s studio, which no longer exists, represented a unique space for thinking and—if you will—a living organism is demonstrated on vintage photographs in the exhibition by Werner Lieberknecht, who was born in Dresden in 1961. They offer us an impression of Glöckner’s studio a few months after his death, when the young photographer was given the opportunity to document the untouched studio during several visits in the autumn of 1987.

Against the backdrop of this selection of works, the question arises as to whether Hermann Glöckner developed his own extended concept of art with specific laws and rules beyond the classical concept of the work, which eliminates the boundaries between “high and low,” shifting him once more into the first rank of innovators among the avant-gardists.