SWISS STAINED-GLASS WINDOW DESIGNS FROM THE RENAISSANCE TO THE EARLY BAROQUE ǀ THE MUNICH COLLECTIO

The Exhibition

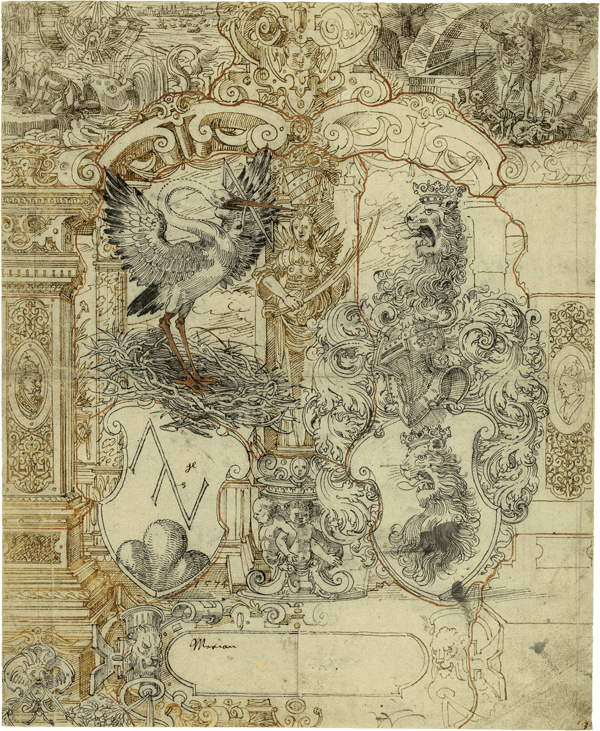

The Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München is home to an exceptional collection of approximately 300 Swiss stained-glass window designs. Around 150 of them were part of the museum’s founding collection. They came from the Mannheim collection of Carl Theodore, Elector of Bavaria, and were probably originally acquired from the stock of working drawings of a Basel workshop. Added in 1921 through transfers from the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum were a number of designs from central Switzerland. Outstanding works from the workshops of the Holbeins, Tobias Stimmer, Jost Amman, Christoph Murer, and many others provide a multifaceted and high-calibre survey of this singular branch of Swiss art.

ILLUMINATED ADVERTISING OF THE MIDDLE AGES

Even during the early modern period glass was expensive. An individual planning to build a home or an innkeeper wishing to renovate his public room, for example, solicited support for the acquisition of a glazed window from the town, his guild, or friends. A successful appeal was proclaimed in bright colors by a stained-glass window, set into a bull’s-eye pane and bearing the coats of arms of the donor, combined with his offices and functions and moralizing inscriptions – an early form of illuminated ‘shop window’ with its appeal to the senses.

The Munich collection contains the most important German collection of stained-glass designs after that housed at the Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, the largest of its kind worldwide. This artistic genre is unique to Switzerland, the Alsace region, and southern Germany. Besides showcasing their aesthetic quality, the exhibition and catalogue provide a cultural-historical contextualization of the exhibited design drawings.

STATUS AND STAGE

The Swiss custom of giving stained glass panels – Kabinettscheiben – as gifts lasted until the early Enlightenment. Soon, however, the emphasis was less on financial aspects and instead on denoting status, the advertisement of social connections, the display of mutual esteem. Everyone gave such gifts, and hoped to receive them as well – abbots, monasteries, municipal regiments, cantons, guilds, bailiffs, but also innkeepers, bakers, and butchers.

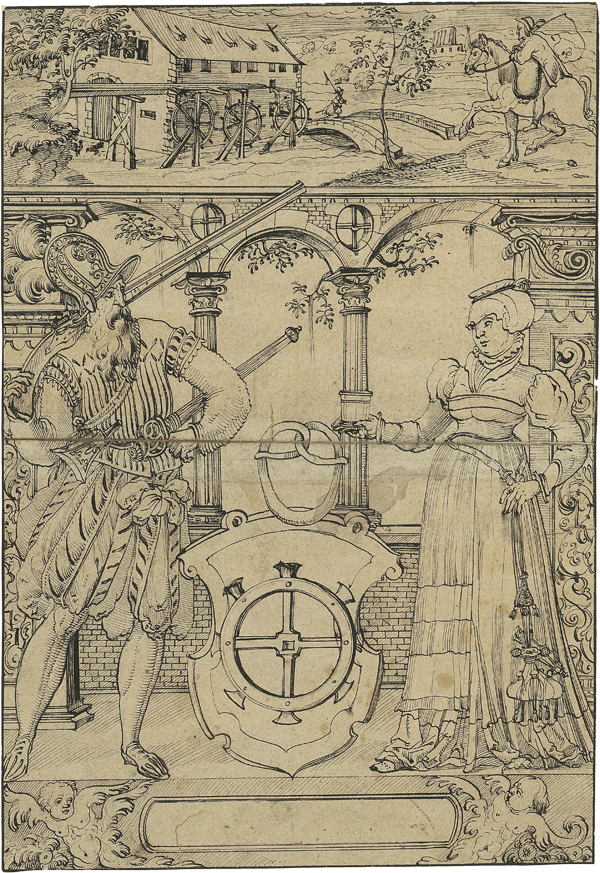

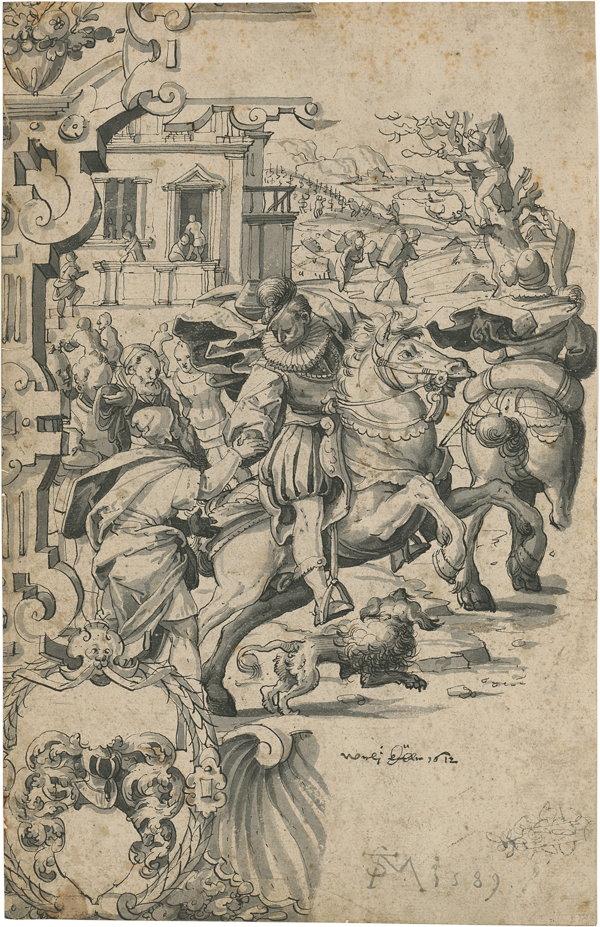

The Swiss traditional freedom to choose and display one’s own coats of arms, which allowed anyone to select their own emblem, ensured the phenomenon a long life. A butcher, for example, would display a bull’s head on his escutcheon, a baker a pretzel, and a miller a millwheel. Nor was it purely a matter of heraldic charges alone. In Zurich, for example, coats of arms were both small and positioned marginally. More important was the central pictorial field, which displayed theatrically staged episodes from the Old or New Testament, allegories, but also incidents from everyday life, an aspect that endows the medium with such significance for the study of cultural history.

Within the prevailing division of labor, glass painters generally received designs, the so-called Scheibenrisse, from specialized craftsmen: these cartoons reflect the exact scale of the final glasswork, most of which are now lost.

Dr. Achim Riether

Department of German Art from the 15th to 18th century

Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München